| Click on any graphic image to see a larger view. | ||||||||||||||

| What was your childhood like? | ||||||||||||||

There were two things about that childhood that helped to turn me into a writer of fantasy. Since we weren’t allowed out after dark (every house in England was blacked out at night, to be invisible to the bombers) and there was no television, I read everything I could find, from fairy stories to Dickens. And since every air-raid was a reminder that an enemy was trying to kill us, I developed a very strong sense of us and them, good and evil, the Light and the Dark. |

||||||||||||||

| What are your ties to Wales? | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| When did you first start writing? | ||||||||||||||

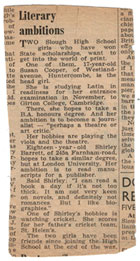

I read endlessly, wrote plays for a puppet theatre operated by the boy next door, and decided at 14 that since adults clearly didn’t understand the young, I should write my autobiography, which would be called Fourteen. It went very slowly, however, and by the time the title had changed to Sixteen I gave up the idea. Instead I edited the school magazine and then went to Oxford to do a degree in English. |

||||||||||||||

| What led you to Oxford? | ||||||||||||||

So I did, with tutorials from the wife of our local vicar—whose house I used a decade later, lock, stock and barrel, as the house of Will Stanton’s family in The Dark Is Rising. The vicar’s wife improved my Latin, and off I went to university, where I spent three of the happiest years of my life. I read English at Somerville College at Oxford University from 1953-55. |

||||||||||||||

| Is it true that Tolkien was one of your professors? | ||||||||||||||

| J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were both teaching when I was at Oxford and without a doubt influenced the lives of all of their students. As dons, they had set the rule that the Oxford English syllabus stop at 1832 and that it be heavy on Middle English and writers like Malory and Spenser, so, as a friend of mine says, they taught us to believe in dragons. They were both often to be seen drinking beer in a pub called the Eagle and Child, known as the Bird and Baby. I never personally met Tolkien or Lewis, and I’d never heard of Narnia, but we were all waiting eagerly for the third volume of The Lord of the Rings to come out, and I loved going to Lewis’s booming lectures on Renaissance literature. Tolkien lectured on Beowulf and was rather mumbly, except when declaiming the first lines of the poem in Anglo-Saxon, beginning with a great shout of “Hwaet!” | ||||||||||||||

| Did you start writing books right away? | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| How did you manage being a journalist and a fantasist at the same time? |

||||||||||||||

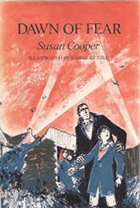

Meantime, between doing interviews with film stars and politicians for the paper, I’d been contributing pieces to a weekly feature called Mainly For Children, and one day the Literary Editor dropped a piece of paper on my desk and said, “You ought to try that.” It was a notice from a children’s book publisher offering a prize of £1,000 for a “family adventure story.” This was more than I earned in a year, so of course I began to write—but by the end of Chapter Two the book turned itself into a fantasy. It became a quest story, full of Arthurian echoes, dealing—though not yet by name—with the Light and the Dark, and it was called Over Sea, Under Stone. I never did submit it for the writing prize. It was published by Jonathan Cape instead, in 1965, after I’d moved to America. I had a feeling that the story would lead somewhere further, but the sequels didn’t happen until much later. Next I wrote a book about the war, Dawn of Fear, which is totally autobiographical except that I turned myself into a boy, and for nine years I wrote a weekly column called “Susan Cooper In America” for a Welsh newspaper. I also wrote a biography of the English author J.B. Priestley. For me, combining journalism and fiction in my writing life worked quite well. |

||||||||||||||

| Why would someone so British move to the United States? | ||||||||||||||

To the horror of my family, my friends and my editor, I had married a widowed American professor from MIT, whom I’d met while doing interviews for the articles; he was 19 years older than me and had three teenage children, and lived in Massachusetts. I was so homesick that when I went home to Wales to visit my parents a few months after moving, my husband later said he was afraid I wouldn’t come back. |

||||||||||||||

| How did you come to write the Dark is Rising sequence? | ||||||||||||||

The homesickness influenced my writing, certainly. Life improved after my son Jonathan was born in 1966, and my daughter Kate 18 months later. I learned to drive, to ski, to cook enormous meals for teenagers and graduate students, and tried (rather less successfully) to understand American football. I returned regularly to England for visits. But my homesickness never went away.

It bubbled up into The Dark Is Rising, a fantasy about the Light and the Dark that is at the same time intensely English, every inch of it set in the part of Buckinghamshire where I grew up. Before I began the book I had realized that it was not only connected—by the Merlin-figure Merriman Lyon—to my earlier book Over Sea, Under Stone, but that they were both part of a sequence of five. So I took a piece of paper and wrote down the names of all five books, their characters, the places where they would be set, and the times of the year. The Dark Is Rising would be at the winter solstice and Christmas, the next book Greenwitch would be in the spring, at the old Celtic festival of Beltane... On another piece of paper I wrote the very last half-page of the entire story, and then I spent the next six years writing the rest of the sequence—and pulled out that half-page when I reached the end of Silver on the Tree. All five books in the sequence were published between 1965 and 1977. |

||||||||||||||

| Did your source of inspiration change after you wrote The Dark is Rising? |

||||||||||||||

After the five Dark Is Rising books, when everyone expected something similar, I wrote a very different fantasy called Seaward. It was written during an awful year when my marriage broke up and both my parents died, but it has hope in it all the same—and one character who still haunts me, a strange little creature named Peth. My book ideas since have all been very different from each other, and gradually I turned my storytelling towards theatre and film as well. |

||||||||||||||

| Did you always write for the theatre as well? | ||||||||||||||

It started with a phenomenon called Revels. In 1973, my publisher brought me to see a performance and introduced me to its creator, the singer-director Jack Langstaff, who cried, “But I’ve read your books! You should be writing for the Revels!” So for the next two decades I wrote lyrics, poems, short plays and stories for those astonishing, joyous celebrations of the solstice. My chapter book The Magician’s Boy is adapted from one of my Revels plays, and I recently published a biography of Jack. I still write small pieces for Revels, most recently for their Welsh-themed performances in 2016. But my longer collaborations were all with my second husband, the actor Hume Cronyn. |

||||||||||||||

| What did you write with Hume Cronyn? | ||||||||||||||

By that time I had accidentally become a screenwriter, because Jane Fonda had liked our dialog in Foxfire and asked Hume and me to write her a TV script from Harriette Arnow’s Appalachian book The Dollmaker (for which Jane, too, won an Emmy.) Then I wrote several other TV films, independently. I never managed an Emmy myself, just a couple of nominations, but I was very happy when the ladies got them. |

||||||||||||||

| Have you worked on other collaborations? | ||||||||||||||

| Every book is a collaboration between author, editor and illustrator. My editor, the late legendary Margaret K. McElderry, paired me with wonderful artists—notably Ashley Bryan and Warwick Hutton for some of my picturebooks, and Michael Heslop and Trina Schart Hyman for jacket art. But I have just collaborated in the creative process fully with an illustrator for the first time—and who better to do that with than the wonderful Steven Kellogg—in the creation of The Word Pirates, a story honoring our late friend Margaret Mahy. Also I’ve worked on musical collaborations with composers, which has been great fun, and on multi-author anthologies. The latest project with the NCBLA, “The Exquisite Corpse Adventure,” was actually a collaborative game, which I encourage young writers to try for themselves. | ||||||||||||||

| How did your other fantasy novels come about? | ||||||||||||||

| At the same time that I was working on screenplays, I wrote picture books—retellings of folktales from the British Isles full of myth and magic: The Silver Cow, The Selkie Girl, and Tam Lin. For a long time I wanted to write a story about the invisible mischief-making spirit known in Britain as a boggart, and suddenly when I was on vacation in Scotland with a friend we saw a castle where I instantly knew my boggart lived! So out of that came two cheerful fantasy novels in the 1990s: The Boggart and The Boggart and the Monster. Twenty years later, I've written a third, because I missed my boggarts so much! It's called The Boggart Fights Back.

Eventually the theatre and the writing sides of my life came together in my head, and I found I wanted to write a story about a modern American boy actor who finds himself onstage with William Shakespeare at the Globe Theatre, in London. At first I pushed this idea away, since I knew it would mean lengthy research into 17th century English life, not to mention Shakespeare, but I had made the mistake of mentioning it to Jack Langstaff, who proceeded to remind me of it enthusiastically at monthly intervals for a year. So in 1998 I finally wrote King of Shadows, and sent the very first copy to Jack.

The next book was a fantasy called Green Boy, which came out of twenty years of visits to the Exuma Cays, in the Bahamas. When one beautiful, untouched little cay came under threat from development, I put both the threat and the island into this fantasy novel. James Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis, which suggests that the whole earth is a living organism, also haunts the book—as it did my very first novel, Mandrake. (You can find the hypothesis in Lovelock’s fascinating books, starting with Gaia.) Having written a timeslip book that gave me the chance to meet my greatest hero, Shakespeare, I thought again about a tiny long-ago incident that had been floating about my head for years. Another hero, if you’re English, is Admiral Lord Nelson, who was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar while helping to save his country from being conquered by France and Spain, and somewhere I had read that the crew of his flagship H.M.S. Victory carried its tattered flag in his funeral procession through the streets of London. As his coffin was lowered into the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, the sailors were supposed to fold the flag to go down too— but they couldn’t bear it, because the flag was all they had left of him. So they ripped it apart, and each one of them kept a piece. I thought: suppose one of those sailors was a ship’s boy, and suppose he kept his piece of flag all his life—and suppose it comes down to the present, to another boy—no, to a girl—and suppose— So I wrote Victory in 2005, about 18th century Sam and 21st century Molly, and it gave me the chance to meet Nelson. After that, I built a house on a piece of the Massachusetts coast where for centuries Native Americans used to hunt, until the invading British appropriated the land 300 years ago. It's a haunting place, and it drove me to write a fantasy called Ghost Hawk. As for what’s next.... Readers often ask writers where their ideas come from, incredulously, as if they already know it must be from an elusive and mysterious source. You can read my essays in Dreams & Wishes for my thoughts on imagination, and creating story. |

||||||||||||||

| Where do you currently live and work? | ||||||||||||||

I live on an almost-island in a saltmarsh in Marshfield, accessible to the mainland only when the tide is out. Here I sit and work, looking out at the Atlantic. On the window sill there’s a magic talisman, a round green glass float once attached to a fisherman’s net, that I rescued from the beach. Not a beach here in America, but beyond the horizon—in Wales. |

|